The saying “a man’s home is his castle” is a bit outdated. It originated at a time when the home was a place where people had private communications and stored their private letters and diaries. Today, people typically keep those types of communications stored on their smartphones.

Paul Revere would not have taken his famous midnight ride if he could have warned his friends that “the British are coming” via group text. And John Hancock would not have abandoned his secret papers if they had been stored digitally (instead of in an enormous trunk that required two men to carry it) when he fled that night.

If our founding fathers could have used a pocket-sized box to dispatch and store their private correspondence, they would have. And they still would have wanted their private papers to be secure from government intrusion. The right of citizens to live free from unreasonable government intrusion was one of the founding ideals of our nation. It was central to two Amendments in the Bill of Rights – the Third and the Fourth – and is no less important today than at our country’s founding.

The Third Amendment

The Third Amendment prohibits the quartering of soldiers in any house, without the owner’s consent. Colonists were required to quarter soldiers sent by the British government, preferably in inns, stables, alehouses, and private homes. In 1765, if Colonists were unable to provide barracks, Governors were authorized to quarter soldiers in inns, stables, alehouses, and uninhabited buildings. After the Boston Tea Party in 1773, Parliament passed a Quartering Act allowing Governors to order British soldiers be quartered in private homes without consent.

It would be hard to keep your thoughts, conversations, papers and effects private when a G-man is literally living in your home. The quartering of soldiers was so detested, it was twice listed in the Declaration of Independence as grounds “to throw off such Government.” Later, the Third Amendment was enacted to prevent this hated and abusive intrusion by the government on the privacy of its citizens from ever reoccurring.

The Fourth Amendment

“The right of the people to be secure in their persons, houses, papers and effects against unreasonable searches and seizures shall not be violated, and no warrants shall issue but upon probable cause … particularly describing the place to be searched, and the persons or things to be seized.”

The United States Supreme Court has recognized that the Fourth Amendment’s warrant requirement extends to information stored on a cellphone, as it does to papers stored in a home. In Riley v. California, the Court determined that officers could not search your cell phone without a warrant simply because it was in your pocket at the time of your arrest. Balancing the small risk of destruction of relevant evidence against the massive amount of personal information accessible on a modern cellphone, the Court held that police must obtain a search warrant based upon probable cause before they search and seize the contents of an individual’s cell phone. (Thank goodness).

Phone Data Dumps Are Not Particular

The Fourth Amendment’s requirement that the government must apply for a warrant by “particularly describing the place to be searched and the persons or things to be seized” arose from another abusive and detested practice the British authorities used on its subjects: general warrants. General warrants gave officials the authority to search and make arrests for a particular crime without specifying who, what, when, or where would be searched, arrested, or seized. In one highly-publicized incident, a general warrant allowed officials to search for the authors of a paper “The North Briton,” after it offended the King and other high officials. By the end of the search, authorities had broken down 20 doors and arrested 49 people, most of them innocent. They had also broken hundreds of locks on cabinets and trunks and had dumped thousands of books and manuscripts onto floors. The particularity requirement requires the government to present probable cause to search specific places for specific people or things.

The Fourth Amendment’s requirement that the government must apply for a warrant by “particularly describing the place to be searched and the persons or things to be seized” arose from another abusive and detested practice the British authorities used on its subjects: general warrants. General warrants gave officials the authority to search and make arrests for a particular crime without specifying who, what, when, or where would be searched, arrested, or seized. In one highly-publicized incident, a general warrant allowed officials to search for the authors of a paper “The North Briton,” after it offended the King and other high officials. By the end of the search, authorities had broken down 20 doors and arrested 49 people, most of them innocent. They had also broken hundreds of locks on cabinets and trunks and had dumped thousands of books and manuscripts onto floors. The particularity requirement requires the government to present probable cause to search specific places for specific people or things.

Unfortunately, the practice of general warrants has reared its ugly head in the digital era. For example, “forensic searches” of cell phones by law enforcement involve the government doing a “data dump” and seizing the entire contents of the phone. As a criminal defense attorney, I’ve had to comb through all the texts and photos contained on a client’s cellphone and then discuss with the client the most sensitive, embarrassing, and private things the phone contained to prepare my client’s defense (because the prosecutors and police were combing through that data for information to use against the client). It is a humiliating process. The United States Supreme Court has yet to decide a case on whether a data dump of an entire phone complies with the Fourth Amendment’s particularity requirement.

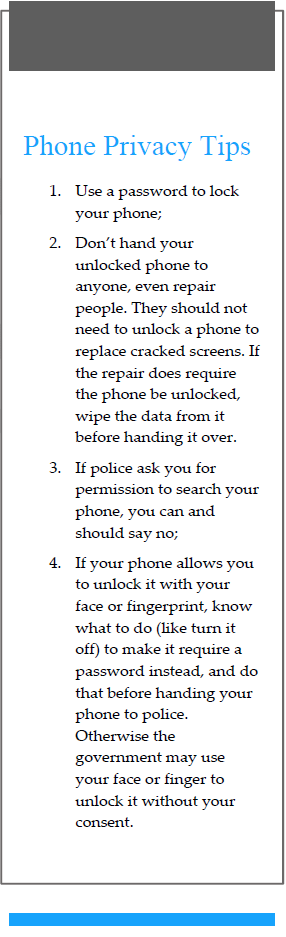

In the meantime, be proactive to protect the data on your phone from outside parties who may try to use your private information against you (see box).

Conclusion

Although technology has changed how and where we conduct and store our private affairs, it did not alter our Constitutional rights. Any government intrusion upon the lives of the people should adhere to the Constitution.

Your Phone is now your castle. Guard it as such.

https://themissouritimes.com/50727/bukowsky-your-phone-is-your-castle/